|

Grief Hue

Heather Carnaghan | July 9, 2020 Early in their studies, someday-educators learn about how the brain absorbs new information. That magical gray matter takes in something new and then sorts it into an existing schema, meaning that we attach every new experience to something we already held to be true. We do not experience information in a vacuum “as it is,” but rather we experience information through the lens of who we already are and what we already believe. When new information doesn’t fit into our existing schema, disequilibrium occurs. This is a fancy way of saying that your brain struggles to piece together a new truth. It can be uncomfortable and frustrating because it means reexamining everything you had previously sorted into that schema through a new lens. Sometimes this new lens reveals something unflattering about yourself or the world you were comfortable in. Profound grief has been the catalyst for the most impactful disequilibrium in my life and has provided a unique schema for examining the nuances of racism that aren’t inherent for someone with my particular privilege. Three years ago was a simpler time in my home. My family’s biggest worry was deciding on a name for the little girl we couldn't wait to meet in a few more months and planning to take two toddlers and a big pregnant belly on an eight hour flight to see family in Northern Ireland. I knew Charlotte, who officially got her name on that trip, would change our world, but I had no idea just how much. When she died, two weeks before her due date, my whole world was sent into a tailspin. Less than 1% of births in the United States end in stillbirth and less than .01% of healthy pregnancies end in unexplained full-term stillbirth. We were the unlucky .01%. I didn’t learn until much later that my odds of having a stillbirth were actually significantly lower - by almost 50% in fact - than my similarly educated, professionally employed, healthcare-holding African American counterparts. Racism is not new in the United States, but the internet has changed how we learn about it. Where racism was once sugar coated with blurbs in the history books about slave owners who took ‘good care’ of their slaves and news reports of ‘Black on Black crime,’ it is now possible to hear first hand from voices that were historically silenced, access infinite records and statistics, or even watch film of a racially profiled man as he pleads for breath. The Bible (Luke 12:48), Spiderman Comics, President Roosevelt, and the French National Convention of 1793 agree that “with great power comes great responsibility.” The internet has imbued our generation with tremendous power and with it comes a responsibility to do the work of examining our own understandings and biases when we find that something doesn’t add up. I have been a public school teacher in extremely diverse schools for most of my career and the narrative I have been told about African Americans - that fathers are absent, that youth are aggressive, and that men are dangerous - didn’t add up to my experience. The countless families of color I had interacted with in my various school communities, the Black colleagues I had the opportunity to work with and learn from over the years, the Black students I had the privilege of teaching, and the Black friends I loved seemed to ALL be exceptions to this “rule”. In fact, in my 37 years on this planet, I have been presented with hundreds of thousands of “exceptions”, and perhaps one or two examples of “the rule”. It didn’t add up. The first half of 2020 has placed racism front and center in American public consciousness. Social media has tipped the moral scales of typically lazy information consumers so they feel responsible to take a stand on this issue. I have been guilty of silence in the past, even when my heart told me there was a clear narrative of bias. That was my privilege, and that failure is a hard one to admit to. Today I lean on philosophy inspired by Maya Angelou’s always wise and beautiful words, "I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better." As I read about and listen to more Black experiences with racism in America, I am struck with a deep sense of empathy that comes directly from grieving Charlotte. The child loss community hosts endless conversations about the exhaustion we feel. It's difficult to articulate how very tangible the weight of death is once you've experienced it in this profound way. Each morning you arm yourself with responses and coping mechanisms for the well-meaning, but piercing nonetheless, exclamations of "Three boys? Don't you just wish you had a girl?" or "It was a rough day, but at least I kept all my kids alive, right?!" Days are laced with glimpses of the children born at the same time - who lived - and quiet reminders of trauma in her siblings who no longer believe the Disney narrative that children are invincible and love brings families back together despite all odds. Nights come with nightmares - my own flashes of those moments, or those of my sons who are terrified of growing older because once death touches you, you forevermore fear for the living who are left. What is simple to someone else - listening to the radio, watching a film - can be the trigger for anxiety in grief. Grief lives in a private place deep in our subconscious. Even the eerily insightful poets, the authors who expertly immerse their readers in this world, and the eloquent lecturers on the subject, struggle to truly articulate the complicated and deeply personal nuances of grief. Profound grief tints every conversation I have, every relationship I am a part of, and every experience I take part in. It is heavy. It is exhausting. It is so frustrating to have to explain this weight to others in every single moment that it is sometimes less exhausting to stay silent, adding that moment to the weight I already carry. This only works until the weight breaks you. And it breaks you again and again. When I hear the Black community say "We are tired," this is what I connect it to. My exhaustion was only born three years ago and it overwhelms everything I do and think. This community's exhaustion was born 400 years ago. It has been shouldered by generations and has had four centuries to fester and grow in complexity. I have had shelter in my grief, but racism on a systemic level doesn't allow shelter. I cannot fully understand how it feels to be in an oppressed culture because mine has been so privileged, but Charlotte has taught me some nuances of that experience that motivate me to always keep trying to be better for, to, and because of the Black community. Grieving mothers, this particular shade of empathy is uniquely ours. It was born in us when our children died. It was fortified each time we silently decided whether to share her or hide away our grief, wondered what she would be today, or juggled the coexisting joy and pain of our “new normal.” This shade of empathy, our grief hue, is the lens through which we can begin to understand the nuances of how racism impacts individual lives. When George Floyd called out to his mother, he summoned all “loss moms” to stand with her. While our own privilege may prevent us from understanding the complexity of the Black experience in America, our grief hue gives us a deep understanding of what it means to always carry something bigger than ourselves on our shoulders. We can dismiss this connection to individuals suffering under systemic racism, or we can choose to lean into it and use it to build a future that is more equitable and kind to all of our children. I choose to lean in with purpose and vulnerability because that is the example I would have wanted to set for Charlotte. Guest Post by Dr. Jennifer Huberty

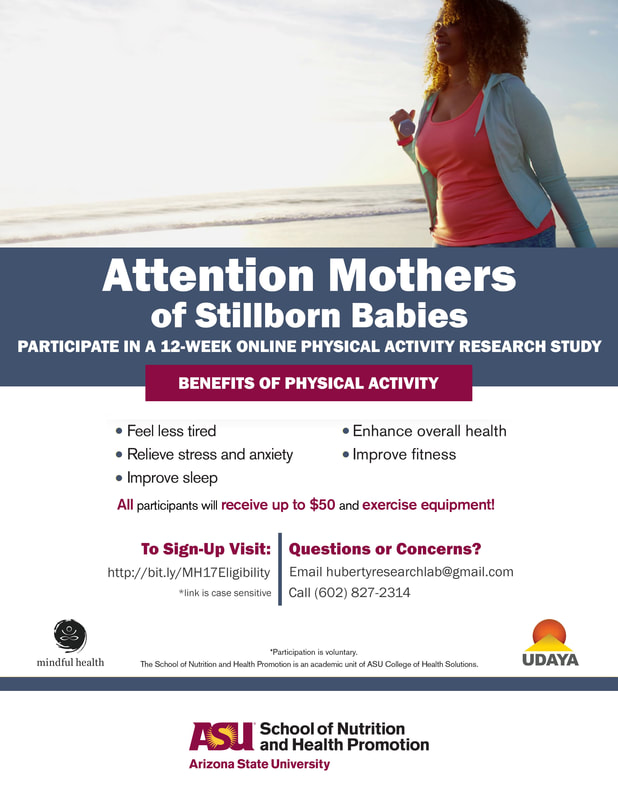

“I can’t wait to hold her and tell her I love her,” I said to my husband as we drove to the hospital to deliver our baby girl, Raine. When we got there, however, the nurse couldn’t find the heartbeat. She left the room and returned with the attending resident who, after looking at Raine with an ultrasound, turned to me and said, “I am sorry, your baby is not alive.” I didn’t cry. My husband did, but I couldn’t. I was in complete disbelief. I received an epidural so that I would no longer feel the pain of labor in my body; I felt it in my heart instead. I cried, threw up, sobbed, and ask why. Raine was so beautiful. Her lips were amazing – so big and round just like her big brother’s. She had a full head of dark brown, curly hair, just like me. She was 8 pounds and 4 ounces. She looked so adorable and so sweet. But she was still. I can’t believe she isn’t here, and I will never know why. In order to cope with the extreme grief that I was having I started seeing a therapist but that wasn’t really helping me. I felt like I was going in circles, asking the same questions, like “ripping a band-aid off” over and over again. I shared this with my therapist and she suggested yoga. I was opposed to the idea of going to yoga at first. I thought, “What is yoga going to do for me?” and “I already exercise.” I decided I would at least try, mainly because I wanted to feel better. I was so sad all the time and had so many emotions like anger, jealousy, depression, anxiety. Shortly after beginning yoga, I couldn’t get enough. I was attending class 4-5 times a week. On the mat I learned to have a relationship with myself, something I desired my entire life but was never sure how to find. I discovered a sense of the present and being in the moment. I found a deeper understanding and appreciation of the practice of patience. In more recent years (it’s been seven years since Raine died) I have learned that it is ok to just “be” with my feelings and thoughts when they arise. I have learned that I don’t have to push them “away” or “down” and that it is ok to cry. I have learned to treat myself with more compassion as well. As a researcher who studies women’s health, I knew I had to incorporate yoga into my research in order to help other moms like myself cope with having a stillborn child. I reached out to Udaya.com, an online yoga website, that I used to practice yoga when I couldn’t go to a studio or wanted to save money. In partnership with Udaya.com I was funded by the National Institutes of Health for a physical activity research study for mothers of stillborn babies. We are currently in the last year of the study and are looking for 10 women to participate in the study. The study is open to women who do not currently have a yoga practice and have had a stillbirth in the last 2 years. This study is 12 weeks, and all participants will receive up to $50 and exercise equipment. If you are interested, please click here to take a 5 minute survey to see if you are eligible. For more information about the study, please email [email protected] or call 602-827-2314. by Heather CarnaghanI fell asleep reading about a boat somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic. I dreamt I was aboard a beautiful ship. Its sails were crisp and white and the skies were impossibly blue. Seagulls squaked. Someone shouted happily that we were on course and my two boys laughed as they chased one another joyfully across the deck. It was the kind of afternoon that you can’t help but lazily close your eyes and smile into the sunshine. In an instant, the sky blackened. The towering mast fell in an explosion of sound. I felt myself abruptly shoved into the sea, dragged underwater and looking around, desperately begging slow motion bubbles to reveal which way was up. My eyes were blinded by the sting of the salt and my lungs burned for air. I gasped as I broke through the surface and frantically looked for my husband and children. In that dreamy way, weeks passed in flashes. My family dodged debris and spit salty accidental gulps as we treaded water in heavy clothes and grasped at driftwood to stay afloat. It was hard to see land through the giant swells. We froze each time pointed fins crept above the water nearby, then disappeared somewhere below. We were anxious about them even as they were out of sight. I woke up panicked, heart racing. I never had nightmares before this year. This one was palpable and disorienting. I still had the taste of saltwater in my mouth. It felt so real that it could have been a memory, but I’ve never been in a shipwreck. Or have I? Perhaps the scene was so familiar, not because of the setting, but because of the feelings it invoked. Our family was on a beautiful course before Charlotte died . We had a new baby on the way, our first girl! Her nursery was perfect. My oldest son and I had painted it together as a love song to his baby sister. Her closet was bursting with the sweetest patterns and the softest fabrics. We had begun planning a trip so that she could meet our overseas family while she still had that baby smell. Charlotte was two weeks from her due date and our world was beautiful. Our sails were crisp and the skies were blue. “I’m so sorry, there is no heartbeat.” Our sky blackened with those words. We were abruptly shoved into a world that we didn’t know existed for newborns. Skin tears, bruises, blood, stillbirth, bereavement, death. There were questions we weren’t prepared to answer. Should we have an autopsy done on our baby? Should we cremate or bury? How much are we willing to spend on an urn? How do you plan a memorial for a baby? How do you tell a 3 and 5 year old that their sister is dead? We grasped at anything that resembled an answer and fumbled to find which way was “up”. Our eyes were raw and salty from too many tears and every thought was of surviving the next minute without her. Our house was a lifeboat adrift and alone on horizonless water. When we first kicked our way to the surface of our grief, we eased back out into the world slowly. Every errand was exhausting. We carried with us pockets filled with tissues, escape plans, and fear of the next well-meant, “How’s the baby!”. We clung to our chaperones, those friends and family members who stuck with us as lifelines even after the tsunami of sympathy cards and frozen dinners stopped arriving at our doorstep. Joyful, living, baby announcements circled ominously, producing anxiety even when they were out of sight. We found other bereaved parents, these voyagers who were battered and changed by their grief too. We held on to their stories for dear life, feeling less crazy that a few months hadn’t erased the feeling of “simply surviving” the bigger waves and still not seeing solid land. My heart slowly returned to a normal pace as I came to an unsettling realization. I had been living this shipwreck dream, this nightmare, for nine months. It just happened to have taken place on dry land. There is an expectation in our culture of moving on, of working through our grief, of transforming this tragedy into something worth the heartache. After all, every fetishised American hero has pulled themselves up from their orphaned bootstraps, right? In reality, we are certainly changed by grief, but the expectation of a happy ending, that place where we are over our loss, is an impossible one. What possible transformation could be worth a lifetime with my baby? There is no real return to normal after your child dies. Your ship is gone and will never be back, so you Swiss Family Robinson your way through each and every day. You forge relationships with locals who know the ways to higher ground. You learn to find physical and emotional sustenance in a foreign land. You begrudgingly become accustomed to the view of coconut trees while silently pining for oaks and acorns. Sometimes a visitor, perhaps a familiar face from Before, looks away uncomfortably as they try not to remind you of home. Do they think you forgot about it? Could they ever forget their own? Trauma physically and permanently rewires your brain. One year ago I was in the sixth month of pregnancy. I was happily painting Charlotte’s name on the nursery wall and selecting children’s books about inspirational women so she’d recognize Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Maya Angelou’s words by her first birthday. I found a perfect “take home” outfit for her on a day that I happened to be wearing a tee shirt that jokingly read, "You’re kickin’ me smalls!” Today, I am in the sixth month of pregnancy again. This time with a boy. Finn’s name won’t be painted on that nursery wall until he is crying in my arms and no outfit will be assumed a "take home" one without the lingering fear that it might become a burial gown instead. I will adamantly insist that no friend or family member throws a shower, as this might “jinx” things. When we talk about Finn, our verbiage is different too. We sang goofily to Charlotte and said, “when you come home...!" Finn hears more solemn, "ifs" and a lot less singing, but he hears a whole ocean of hope. I can’t expect a traditional Disney happy ending. No baby will replace the one I lost, but I am hopeful that we’ll at least have an interesting next chapter with a new life that adds a sparkle of sunshine to our waves. Charlotte's stone in the tide (Crane Beach, Ipswich). Photography by Pam McRae

by Heather CarnaghanToday I should be distracted from my writing by a nearly mobile, chubby cheeked eight month old. Instead, I sit in silence reflecting on the extensive grief resume that I’ve built while sitting in a rocking chair next to a crib that has never been slept in. When I walked into this nursery eight months ago, I sat slumped on the floor staring at Charlotte’s name painted across the wall for hours. I remember thinking, “now what?” Without recognizing it, even in that minute I had begun to build a grief resume. I started from the bottom, right there on the nursery floor, where everything is a minute by minute battle. I dressed stitches and researched ways to soothe engorgement without a baby to nurse. This hodgepodge collection of resources started on post-its, as bookmarked websites, and dog-eared pages in stacks of grief books given to me by well-wishers. My husband suggested organizing it into a website so I wouldn’t lose anything. This seemed like a reasonable thing to focus my energy on, so I created the very first page on CharlottesPurpose.com, “Maternity Leave Without a Baby”. I started writing. I began a journal of letters to Charlotte and wrote poetry in those minutes where sentences were hard to string together. Authoring an idea in this way made me feel as though I had accomplished something. I had recorded a raw feeling exactly as I felt it so someone else might begin to understand. Corpse Color The day you were born still and silent my heart was shattered into fragments so sharp that they pierced through my whole life leaving wounds that will never heal. I held your tiny hand and stroked your chubby cheeks. They grew cold as my own warmth seeped out of you and the corpse color crept over your perfect toes. Due Date All of the broken promises of this beautiful and awful date ae heavy in a place in my heart where, now, there only exists stolen hope. Who I was and who you would have been died that day and left me with all the parts of motherhood that the drug of a newborn’s smell subdues. How cruel it seems that I also have this love that is so deep that I will take all of these awful things if they are all I am meant to have of you. Grief Grief, like a mountain is born from the crashing of two giant tectonics that shouldn’t meet but do so with such force that the whole earth crumples at that fault line, an accordian fold that cannot be flattened again despite our monumentous human efforts. A theme emerged in my writing. There was despair, certainly, but there was also hope. New Growth The blinding, slashing rain of this wretched storm will pass and it its wake new growth will rise up from seeds I never knew I planted. Jack Pine the humble Jack pine whose seeds are born in wildfire this phoenix of trees Forward Forward. Mechanically we march, battered, but vaguely certain of a thicket ahead with less thorns. I began writing our story. In that first month I was horrified that I might forget even a tiny detail about my daughter’s life and I knew that was all I had. So I wrote. And wrote. A paragraph became a chapter, then a book.

Meanwhile, CharlottesPurpose.com was growing. I had continued to research support systems, grief resources, and the science of stillbirth. The site exploded from a single page to ten, then twenty. One day I was clearing out a room with the plans of turning the old office into an art and yoga studio to help with the healing process. I came across my wedding dress and cried because she would never wear it. When I had no tears left, I noticed a long-forgotten sewing machine in the corner. It had been abandoned years before when I realized that I couldn’t sew a straight line for a pair of curtains. An idea formed slowly as I layed rubber yoga flooring and lined up the art supplies in neat rows. The Youtube sewists said creating an infant gown was “easy”, so I plugged in the sewing machine and stole an old bed sheet from the linen closet. My first attempt looked like a kindergarten art project, but by the fifth, seams were lining up. I forgot what my wedding dress had looked like. An enormous chapel length train flooded out of the box as I lifted it from the preservation box. The fabric was smooth and elegant, perfect for a baby’s burial gown. I clipped a block of fabric off haphazardly so that I couldn’t chicken out, then traced the very first pattern for The Wrapped in Love Project. Soon I had donated wedding dresses flooding in faster than I could repurpose them and three new sewists joined the project. While grief engulfed me and made me desperate to stay still, Charlotte gave me direction and meaning. Each day- even on the worst of them- she forced me out of bed to get her brothers ready for school. She wouldn’t let me sit idly in my sadness when there was a website to build, a story to tell, and a wedding dress to repurpose. One week before her memorial, I was abruptly given a tiny window of time to apply for a job I had worked for several years toward. I got dressed that day, not in the sweats that had become my uniform, but in clothes that I would have worn to work. I’m not sure why, really, except that I needed to feel as though I was truly the person in the resume that I was compiling, and I wasn’t convinced that person still existed. I was granted a meeting and interviewed with a panel of six stoney faced principals who didn’t know that I clutched a fox stone so tightly under the table that my knuckles were white and the engraving left an imprint in my palm. They didn’t know that I had given birth to, and cremated, my child less than two months before, or that every answer I gave was followed in my head with, “Can I really lead a school brimming with living children when my own is gone forever?” I smiled, genuinely glad to be finished, and thanked them for the opportunity that I doubted would be extended. Three days later, I opened an email congratulating me on being admitted to the pool of Assistant Principal candidates. I had never faced a panel interview before this year, but in less than six months as a grieving parent, I managed to be summoned to intimidatingly large panels twice. My principal nominated me for the Teacher of the Year award, so I was asked to interview at the head of a massive table with twelve principals and school leaders. Once again the fox stone was present and heavy in my pocket as I considered their questions. While interviews are uncomfortable, they are predictable. You can expect the handshakes, the stares, the quick fire questions. What a non-loss parent might find strange is that celebrations and gatherings are far more stressful. Small talk always leads to “How many children do you have?” That seems innocuous enough, except that the loss-parent is faced with the dilemma of either being the ‘downer’ in the room or dishonoring their child's existence. These events can be as big as an awards dinner where you are expected to give an impromptu speech to hundreds of people, or as small as an annual community barbeque (dripping with baby girls) that I happened to be pregnant with my daughter at the year before. My eight month grief resume includes new skills like resilience, poise under pressure, metal stamping, and website design. It lists triumphs like parenting two grieving toddlers, returning to work and writing curriculum from scratch, incorporating a small business, and starting the 200 people strong Bereaved Optimist’s Book Club. This eight month grief vitae includes raising $3,000 for a Cuddle Cot, sewing more than 70 infant burial gowns, weathering countless milestones, and conceiving another child. It includes a new network of colleagues and world changers, all unique in their own loss experience, but united in their insatiable will to survive it. Each of our grief resumes look different. Some loss parents have forged cross country moves to escape the sight of painful triggers, others have built altars filled with mementos of a tiny life. Generosity abounds in this community of loss; weighted bears, care packages, and Cuddle Cots are donated in babies’ memory in the hopes that these things might soften the blow for someone else, even for a single moment. They run races, and host fundraisers so that even one family can avoid the fate that they have been dealt. When we are in the deepest, darkest parts of our grief, it is hard to see that the seeds we are planting are taking root. It took me eight months to realize that I have indeed made growth. From this vantage point, it is easier to see that my loss did not weaken me at all. It made me a more appreciative and attentive parent. It made me a more generous and genuine human being. It made me a pillar of resilience. When my baby died, I was given a blank page instead of Charlotte’s life story. It’s my job to write it for her, and I am proud of this first chapter. by Heather CarnaghanI love a good metaphor like some people love a good movie.

I’m a lover of poetry and prose because of those visceral lines that are drizzled with delicious language and playful words that stick to the roof of your mouth as you read them. Yum. A good metaphor can make me look at a simple mosaic and realize that rebuilding after something has shattered can be beautiful in ways I never anticipated. I’ve found symbolism in everything along this grief journey. Today I attended a fancy luncheon at the state board of education. I wore a tiny orange fox pin that was almost hidden by the pink carnation corsage that the host pinned to my dress. In floriography, the study of flowers, meaning is often attributed to particular blooms. There is an old belief that pink carnations grew from the fallen tears of the Virgin Mary. The flower doesn’t drop its petals as it dies, making it a symbol of a mother’s undying love. "That's a funny choice for a celebratory corsage, " I mused to myself. Yesterday I went to the thrift store. I wanted to find camping themed furniture for the new baby’s room, but froze in the parking lot as I realized that the last time I was here I was shopping for my daughter. Through tears I said aloud, “Everything is so cold and dark without you, Charlotte. ” When I collected myself enough to walk through the door, a display immediately caught my eye. A tiny ceramic sleeping fox sat atop an old fashioned wood stove (warmth) with a woodsy lamp stuck atop it (light). Coincidence? Perhaps, but I piled those three items into my cart and was able to continue my search. Months ago, when I finally left my grief thick house and returned to the distractions of teaching 8th graders, my coworkers filled my classroom with foxes. Fox stickers, a fox pillow, fox cards. They knew that I had slammed on my brakes to avoid hitting a fox just after Charlotte died. The creature stopped in the middle of the road and stared at me for a terrifically long time before allowing me to proceed to the hospital. I learned later that two other family members experienced similarly odd fox encounters that same day, but in different cities. My oldest son happened to come home wearing a fox shirt the day we had to tell him that his little sister died. This symbol was so powerful to me that I (who had once said, “there’s nothing so permanent in my life that I would tattoo it onto myself”) had a little sleeping fox tattooed on my wrist so that I’d always have a symbol of my daughter present with me. Foxes hold meaning for me and my family. So, when you text me a picture of the fox that runs across your yard, the tee shirt you found in Target, or the name tag for one “G. Fox” at your convention, what does the fox really say? It says, “I don’t have the words to speak about something as horrific as the death of a baby, but I want you to hear the closest approximation of her that I can muster up.” It says, “I can’t begin to know what you are going through, but I care about you enough to acknowledge that you’re going through it.” It says, “ I think of you, and I think of her too.” Fox sightings remind me that I am not alone in remembering my baby girl, and that I am lucky enough to have a community that surrounds me with love even when the right words are hard to find. Every loss parent has their own “fox”. For some it is a butterfly, a biplane, or a particular shade of purple. If you know a parent who has lost a child, ask what reminds them of that little one, then let them know when you come across it, no matter how silly or insignificant the gesture seems. (I still have a single paper plate that a friend saved for me because of the smiling fox printed on it.) Those signs and symbols let us know that you are thinking about us. They are our version of finding the high school graduate’s kindergarten artwork in an old bin of memories. They are a flicker of who our child was. To see a few fox sightings by our friends (or to add one of your own!), check out “Charlotte’s Journey”. by Heather Carnaghan

On April 21, Charlotte will have been missing from my arms for six months. Half a year of sleepless nights have given me a lot of time to ponder some pretty big thoughts. I’ve thought about religion and science. I’ve thought about loss. But mostly, I’ve thought about love. When it is dark and silent, I think about religion, because in my loss religion has often felt dark and silent. Sometimes it’s a lonely silence, and other times it feels meditative. I wonder where she is. I don’t believe in a golden heaven floating on clouds (though so often I wish that I could). I doubt a 5 pound, 11 ounce winged angel with her brother’s nose and mommy’s red hair is watching our shenanigans from above. I do, however, believe that there is more to us than our fragile one-time-use bodies might suggest. I believe this because I see evidence of it everywhere that I look. A glass of water that sits on the counter is liquid, filling its container with a glorious ability to quench thirst and taking up a measurable amount of space. Yet that same glass of water, when heated to a high degree, turns into steam. Is it gone? No. It is invisible and dissipated back into the infinite universe; those billions of molecules that once made up a unique glass of water will likely never collide again in exactly the same way, but not a single particle of it is gone. I believe that pieces of Charlotte surround us. Her soul is recycled into our entire existence just as her body has been recycled back into the earth; my daughter is physically and metaphysically nourishing new life. When religion exhausts me, I think about science because it seems more concrete and visible. There is a great deal of science that surrounds grief and loss. A 2012 study found that your risk of heart attack is increased by 21 times in the day after a loved one’s death. Takotsuo Cardiomyopathy, or “broken heart syndrome” happens when your heart chambers balloon due to high levels of stress and prompt symptoms much like a heart attack. Stress wreaks havoc on the bereaved. The stress hormones that help us in fight-or-flight situations, hurt more than just our hearts over long stretches of time. Neuroscientists have found that prolonged periods of depression can stop neurogenesis, the process by which we form connections needed to learn and remember. I remember feeling like my brain was “holey” in the early days, like I couldn’t remember what day it was or if I had eaten recently. I once forgot my best friend’s name while I was on the phone with her. That same high level of cortisone that makes the bereaved’s memory spotty, also depletes their immune systems by impeding the production of white blood cells (the hungry blobs that gobble germs in middle school animated biology videos). So how do the members of my awful club keep cortisone in check? Well, with love. More than anything else, in those long, insomnia-laced nights, I think of love. Not the light, airy, eyes-meet-across-the-room kind of love, but the deeper, I’d-die-for-you sort. Without fail, every bereaved parent that I have met has a primal need to “do something” to express this love for their child that is so intense that even death couldn’t stop it. They write love letters to their lost babies. They light candles and donate to causes. They tattoo their child’s name into their skin. They lift up others in the loss community through care packages and hours spent crafting memorial necklaces, bears to fill empty arms, cards, and burial gowns. They do acts of kindness to spread a little bit of love in a world that can feel void of it when the casseroles stop arriving on our doorsteps. This community of those who have experienced arguably the biggest loss one can endure are some of the most generous and resilient people I have ever known. They reach out in kindness because they have found, like I have, that the positive feelings that we spread to others return to us and lighten our burden, if only for a minute. And, in grief, a minute of respite is worth the many hours of service we paid to get there. In our pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps culture, we tell ourselves that the strong don’t need anyone. The hero stands on the pedestal, alone. The cowboy rides off into the sunset, alone. The truth is, I need a lot of support right now and will probably need a lot of support for a long time. I know I can’t do it alone so I solicit help in a sneaky way. I ask you to stand beside me in helping others. What’s sneaky about this? What you’re really doing by joining me in service is standing by me, supporting me. Resilience and depth are traits that I am cultivating, one sweat-drenched step at a time. I am learning that love will get me so much farther along that journey than any drug, therapist, or grief sherpa might. Here are a few “love projects” that I’ve been working on in the last six months so that I can channel my love for Charlotte into healing for me and others in the loss community. Thank you for supporting me as we lift up others through each of these projects. LOVE PROJECTS FOR CHARLOTTE CHARLOTTE’S PURPOSE My biggest labor of love has been a website choc full of grief resources, projects, and support for families who have experienced stillbirth. Charlotte’s Purpose will be working toward gaining nonprofit status this year to further support all of our projects. How you can get involved:

WRAPPED IN LOVE PROJECT This project repurposes donated wedding dresses, formal dresses, and even some menswear into burial gowns for lost babies. I started it with my own wedding dress and have since had 62 more donated. With a tiny team of sewists, we have already donated 29 burial gowns & pockets and 26 more are ready to be packaged and delivered! How you can get involved:

CUDDLE COT FUNDRAISER A Cuddle Cot is a cooling device that allows families of stillborns to have extra time with their baby. Our GoFundMe Fundraiser aims to raise $3000 to donate a Cuddle Cot to Holy Cross in Charlotte’s honor. How you can get involved:

BEREAVED OPTIMIST’S BOOK CLUB This is an online book club that aims to share, discuss, and discover books that help us navigate our unique grief as positively as possible. I started this club after a long search for grief books that were uplifting, tailored to baby loss, and supported my healing. I found that the discussion I had with others as I asked for good book recommendations were just as valuable as the books themselves. How you can get involved:

KINDNESS TAG! We “pay it forward” with acts of kindness in honor of Charlotte and leave a special card behind to encourage others to pass the kindness on. How you can get involved:

Dear Labor and Delivery Team,

First, thank you. Thank you for doing a job that requires so much of you. Those long shifts, full of running back and forth between rooms with the responsibility of so much new life on your hands, can’t be an easy burden to bear. I am in awe of your ability to counsel, coach, and console an entire wing of crying mothers and crying babies. Sometimes the babies don’t cry, and that is hard for you too. No one goes into your field thinking, “I’d like to deliver stillborns”, but it is a devastating truth in 1 out of 160 delivery rooms. My daughter, Charlotte, was stillborn on October 21, 2017. Her heart stopped beating for unknown reasons at 38 weeks gestation. My stillbirth experience was a mixed one. It was 3am when I came to the hospital, alone and worried about my baby’s decreased movements. The nurses who checked me in and set up the doppler were were honest, but gentle, saying that they were having trouble finding the heartbeat and were going to call the doctor to do a sonogram. My own OB-GYN happened to be on call that night. She teared up when she said, “I’m so sorry, I can’t find her heartbeat.” This life shattering news was delivered in the kindest way possible. She apologized, not in an admittance of any guilt, but as a mother showing compassion to another mother. She acknowledged my baby’s gender. Hearing “her heartbeat” was important to me. It spoke of this doctor’s respect for my child and the hug that followed spoke of her respect for me. There were many times after this moment in which that tiny word was replaced with “it” or “he” and each one stung. It might seem like a silly mistake to someone who has never lost a child, but chaplains, nurses, doctors, and even cleaning crew made it over and over that day. Each one told me, “your baby doesn’t matter” by forgetting that Charlotte was a she. One nurse went to get me a blanket (I was already shivering uncontrollably from shock) and another went to get a wheelchair. My doctor asked if there was anyone I could call and explained that I would be induced to deliver. I was wheeled to a room at the very end of the labor and delivery wing. It felt like a cruel place to put me, passing room after room of happy conversations and bright balloons on our way, but I realized later that this was a purposeful placement. My labor was loud and awful. My screams were hollow and sad. New moms with crying babies didn’t need to hear my sorrow and I didn’t need to hear their joy that day. I didn’t hear a single baby cry during my stay at the hospital- not mine nor anyone else’s. That gave me the quiet space to focus on my own grief and how I could survive this storm. My husband and mother sobbed with me in the room, and probably more profusely outside of it. I wish that there had been a place for them to go. They were rushed from the hallways when they stood there too long, but they needed moments away from the agony of my room as they began to process their own grief. My mom took to walking the halls so she wouldn’t be scolded for standing outside of the delivery room. She took a wrong turn near the NICU door and a nurse joked, “you don’t want to go that way!” before pointing her toward labor and delivery. In another life, she would have chuckled along, but that day she wished more than anything that she could visit the NICU. Small comments like these etch themselves onto your heart when you are grieving a child. The most hurtful ones dismissed my baby as unimportant. A cleaning crew member congratulated me on the baby while I was still in labor and, when I tearfully said that she would be born still, she said, “you’re young, you can try again”. I sobbed because I wanted this baby, my baby that I had waited 38 happy, healthy weeks for. A nurse asked if I was “a believer”. My beliefs are my own and were so complicated by this experience with infant death, that I simply said “no”. She continued with “well I believe…”. Those three words said, “You’re wrong. In the depths of your despair, what you believe is wrong.” The platitudes she shared were unwelcome and insensitive. Though your hospital has religious affiliations, not all who enter it share them. I hope that, after reading this, staff will consider their words very carefully. It is so much kinder to say, “I am so sorry that your daughter passed” or “There are no words that can take this pain away” because there simply are none. I have spoken to many parents who have lost a child and what each agrees upon as most helpful is a caregiver who listens and acknowledges that this child was important. One nurse who was with me until just before the delivery talked to me about my job, my living children, my family. She asked me about my baby. How did you pick her name? What was your pregnancy like with her? Did you bring something special for her to wear? She used Charlotte’s name when she spoke of her and told me that she would think about her when she remembered to hug her own son a bit tighter that evening. This nurse held my hand when I started to cry and answered my questions thoughtfully. When I asked about donating Charlotte’s organs, she was honest, but gentle as she explained why we couldn’t do this. I am so grateful to her for giving me a small glimpse of what to expect in the hours to come. Despite enduring a long labor, I was not prepared for many aspects of stillbirth. My own doctor finished her shift shortly after my arrival and, in that 27 hours, the doctor who delivered Charlotte only visited to introduce herself and then for several minutes after my husband had tracked her down, desperately asking for a C-Section to put us all out of the agony of labor and waiting. I wish that the delivering doctor had prepared me for the fragility of my baby’s skin or the blood pooling in her lips when she was born. I wish that she had realized that, though my baby didn’t need her that day, I did. I needed reassurance that I could indeed survive this natural birth and this very unnatural grief. My husband needed reassurance that he wouldn’t lose his wife along with his baby that day. When Charlotte was finally born, the doctor asked if someone could hold “the baby” while she stitched me up. I refused and said that I wanted to hold her while she was warm. The doctor rolled her eyes and continued chewing the gum she had during the whole delivery. Had I not already been at the very lowest place in my life, perhaps I would have mustered up the strength to express my disgust. After we held Charlotte for that hour, the doctor stitched me up and I never saw her again. I was surprised that no doctor visited to check on me before I was discharged only 12 hours after giving birth. I wasn’t prepared for how quickly my child would lose color, plumpness, and warmth. A photographer arrived to take pictures of Charlotte, but I didn’t have anything prepared for her because I didn’t know that they were coming. We spent precious minutes of the single hour that we held our daughter searching for an outfit in our suitcase. Had I known that the photographer would arrive after birth, I would have set this out during labor. My mother gave her cross necklace to the photographer. I didn’t know this until we received the pictures later that day and each had this symbol draped over my baby or clasped in her tiny hands. I’m glad that I took my own pictures because those cross-filled images are disturbing to me. I don’t blame the photographer, she was simply listening to my mother, but I do wish that she had listened to me, Charlotte’s mother, instead. I was moved to a room without a baby cot and visited by another nurse and a counselor. They were both kind and sincere. The counselor listened to us express our disbelief and profound sadness over losing our baby girl. Her words preserved Charlotte’s dignity and acknowledged that she was so very important to us. We wished that we had been able to meet with her during the long labor so that we could have better considered some of the overwhelming options that were presented. Burial, cremation, autopsy...these are not things that you are prepared to face in the best of times, much less an hour after sending your baby to the morgue. When we returned home without our daughter, our lives were forever changed. I have learned that helping other people survive the trauma of stillbirth is something that I am passionate about, something that begins to fill the gaping hole of Charlotte’s loss. I created “Charlotte’s Purpose”, a website dedicated to positively dealing with grief, in an effort to heal my own heart but it has already become something bigger. It is full of the resources that I found helpful in this journey as well as a project initiated in Charlotte’s memory. The Wrapped in Love Project is a program in which we take donated wedding dresses and repurpose them into burial gowns and pockets for babies lost before, during, or shortly after birth. This first batch is made from my own wedding dress and many of the gowns currently being repurposed were donated by mothers who have lost a child to miscarriage or stillbirth. I hope that you can help me by offering these gifts to bereaved families. It is my sincerest hope that sharing my experience with you and starting the Wrapped in Love Project will make the next mother who faces stillbirth at this hospital feel some comfort in a moment that is likely her worst. Thank you for all that you do and all that you strive for, Charlotte’s Mom The preceding letter was by Heather Carnaghan and was included with the very first donation of infant burial gowns through the Wrapped in Love Project. For more information about the Wrapped in Love Project, or to donate a dress or time as a sewist, please click here. by Heather Carnaghan

I had the opportunity to share my “message as an educator” to an impressive panel of folks today. When I first learned that I would have this platform, I was stumped. What was my message anyway? I knew my beliefs as an educator. I believe in the power of inquiry to inspire lifelong learners. I believe that all students deserve a stellar education in a safe, engaging environment. I believe that teachers have the ability to instill confidence and purpose along with skills. But...my message? I wasn’t certain how to articulate that. How do I encapsulate all that I am and hope for when that changed so radically five months ago? I’m still taking baby steps in this new normal. My message was as jumbled as one of my three year old’s stories. I decided to let it marinate for a while. Two days ago, I woke up at 3am, like I always do on an anniversary of her death. It was the five month mark after losing Charlotte and I realized that my message wasn’t complete without her in it. I wrote, erased, and cried, then wrote some more. As I poured out my augmented soul onto paper, a message began to float to the surface. I quickly printed it before I could change my mind and stuck it deep into my school bag. It crumpled as it wedged between a thick file of papers to grade and a to-do list that is so long that it has its own notebook. At 11:35 this morning, I stood in front of the panel, fished out my ragged paper, and read. I read how I teach a unique class that links curriculum across the subjects and that those connections matter. I read that my current class of eighth graders was particularly special to me because we have spent two whole years innovating together. They were eagerly counting down to Charlotte's appearance from the moment they first noticed my baby bump as seventh graders to her final weeks in October when we laughed at her kicks, clearly visible through my shirt. I read that we laughed together a lot, and those connections matter. I paused, taking in a sharp breath and preparing myself for the next words on the page, then told them that my daughter was stillborn two weeks before her due date. My voice cracked as I continued. I told them that despite my experience and degrees and past, grief made me feel that I had nothing left to offer my school. I told the panel how my amazing school community offered me a new beginning in the form of handwritten notes and homemade meals. Coworkers donated their wedding dresses to the Wrapped in Love Project (which repurposes wedding dresses into burial gowns for stillborn babies) and a grief resources website called Charlotte’s Purpose, both of which I started in an effort to heal. My students wrote letters with powerful words like "I love you, Ms.C", and "You’ve greeted me at this door for two years and that made me happy for two years. Now let us make you happy for two minutes." Those connections matter. My mouth was dry, but I went on. I told the story of a fifth grade aspiring writer who made me realize how important teachers can be in a child's life. Long after we shared a classroom, he invited me to his Eagle Scout Ceremony with thirty of the people he felt most cherished and inspired by. I was one of his thirty! Those connections matter. The panel stared at me for a pregnant moment. Some let the hint of a smile or a subtle nod escape past their stoney exteriors. I sat up a little taller and swallowed down the anxiety that had made my mouth cottony and my voice waver. Charlotte taught me so many things in her short time with us, but the most important is that every connection we make is one that matters. Whether a family member, friend, student, fellow loss-mom, or stranger on the street, we all deserve kindness and opportunity. We all have the ability to be "one of the thirty" for someone else. I am so very lucky to have had a baby girl who made that message crystal clear to me. "My Message" is published on the Anne Arundel County Public Schools' website through a project called "Faces of AACPS" You can read it here. By Heather Carnaghan

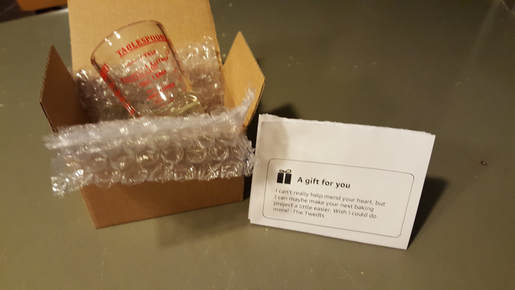

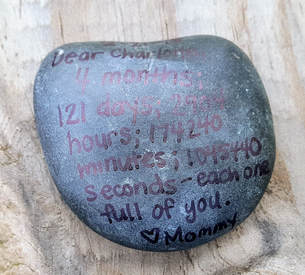

I was washing dishes this morning. I took on this insurmountable task because I had no other options. Every dish in our house had been used and strewn into the already full sink, forgotten on dresser tops, balanced in towers on tables, or lost in the black hole of our playroom. This might be surprising to people who know me well. Before hurtling into this grief journey, I was deeply bothered by messes and clutter. Pans were stacked neatly in their cupboards and all my tupperware had lids. The same four sets of dishes were in rotation over and over. Use. Clean. Put away. Repeat. Dishes were the first chore to evade me when we our daughter was stillborn. The piles started slowly, living outside of the periphery of our concerns. In those earliest days, we barely ate. Food was brought to us in ready-to-trash containers. No cleaning necessary. When the boys were hungry, we served them donated meals on paper plates and fast food right from the boxes. As time passed, we began to use our dishes again. The mugs made an appearance for tea and coffee first. The silverware shyly began to mingle with our fast food plastic and cardboard. Then one night, I made dinner, a real dinner. It had been two and a half months since we’d abandoned our kitchen, relying on friends and Chipotle for meals. I looked through cupboards that I had forgotten existed. My Kitchen Aid, whose edges were still crusted with the cookie dough I had mixed the day before losing Charlotte, stared on, lonely and neglected. For two hours I struggled to read directions, add simple fractions (½ + ¼ is a doozy when you’re grieving), and keep from crying long enough to finish the dish. We ate on real plates that night. Those plates and pots, cups and cutlery all got thrown into the sink. Meal after meal, the cooking was as much energy as I had in me to expend, so the dish tower grew. And grew. This morning I had searched high and low for a plate to put Sam’s breakfast on. When all of the usual places proved fruitless, I snatched a Curious George emblazoned toy plate from the kids’ kitchen. Sam was delighted. I was confused. Where had all my plates gone? I moved a handful of dishes from the sink so I could get to the faucet to pour myself some water. Oh. I started scrubbing. Thirty dishes deep, I picked up a well-worn measuring cup. It was a glass Pyrex with red markings down the side. It was the smallest in a set of five. They all stack inside of one another neatly (a remnant from my tidier days). I washed and rinsed it, then set it in the drying rack...only it didn’t stay there. The measuring cup slid out of my soapy hands and crashed to the floor, scattering shards across the kitchen tiles. In another life I might have chastised myself for being a clutz before sweeping the bits into a dustpan, but today I cried. My body collapsed to the floor and my eyes welled up with big, sloppy tears that made it hard to see. I sobbed over this measuring cup, this tiniest-of-five, fragile little thing that was so necessary to my kitchen and now was gone in the blink of an eye. Grief is messy and mean for loss parents. There’s always something to clean up, whether it is dishes or another heartbreak. Showers become judgement-free cry sessions and our cars confessionals where no one hears us scream. Walls and pillows take blows from our angry fists and unused baby blankets catch plummeting tears. There are leaky noses, drippy mascara, and dishes in the sink. There are always dishes in the sink. Sometimes the small pains- the baby announcements we face with a forced smile, the strangers who ask “how many kids do you have?”, the call to support a new loss parent- add up until they are overwhelming. Just like the loss itself, we don’t always see these moments coming. They throw us backwards by miles when each step forward is miniscule and hard fought. It is at these moments that a measuring cup isn’t just a measuring cup. It’s my measuring cup, and now the stacking set makes no sense and I’m stuck measuring ⅛ cup of flour with a 2 quart goliath cup. I’ll survive it, but it takes SO much more effort to do so. Eventually, I did sweep up the glass shards. I wiped my face , finished washing every table setting we own, and for two glorious hours before lunch time there were no dishes in my sink, nor tears in my eyes. UPDATE: I don't usually update my blog postings, but something happened today that made my story feel "unfinished". A package arrived in the mail, small and unassuming, with a big message of hope. "I can't really mend your heart, but I can maybe make your next baking project a little easier. Wish I could do more! -The Twedts" Tucked behind this kind sentiment was a tiny glass measuring cup with little red markings down the side. It looks a little different than the one that shattered, but it brought a big smile to my face. Grief is complicated. Sometimes a measuring cup can break you, and sometimes it reminds you that you've got some pretty great company on this rocky uphill trek. Now, if you'll excuse me, I have some chocolate chip cookies that need to be taken out of the oven. by Heather Carnaghan Today was the four month anniversary of Charlotte's stillbirth. Four months. 121 days. 2,904 hours. 174,240 minutes. 1,045,440 seconds without my daughter in my arms, and yet and every single one has been brimming with her. I went to the woods today, like I always do on the 21st, to find something. I never know what it is that I am looking for when I start my hikes, but I always manage to find it along the trail.

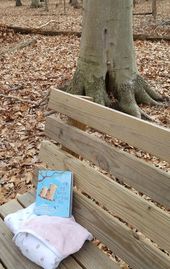

I sat under a tree with scars and proud branches stretched out to catch the season's first real warmth. It had a date and name carved into it just like I did. I laid Charlotte's pink blanket across my lap and noticed a sapling that had rusty crinkled leaves so similar to the proud mama tree whose roots pushed out of the earth and made my bench uneven. I pulled the book out of my backpack and began to read in a whisper, "I'll Never Let You Go by Smriti Prasadam-Halls". How embarrassing it would be if another hiker witnessed this odd display! "I've heard of tree huggers, John, but this woman was reading baby books to acorns." After long glances down the trail in either direction, I read on a bit louder, "When you are happy, I hear you sing." Does she? Mothering a baby who is not in your arms leaves you feeling so much loneliness and guilt. Am I dishonoring her when I laugh? When I sing? When I forget for a split second how much it hurts to go on without her? Am I failing her by fighting my way forward, away from her? A bird watcher approached. I paused awkwardly, "Hi...I'm, uh, just...reading." His eyes darted left and right and down before motioning forward and muttering something about a woodpecker. I watched him scuttle out of sight before I continued reading. "When you are sad and troubled with fears, I will hold you close and dry your tears." The wind picked up and the wetness in my eyes evaporated into the gust. This is what I love about the woods. There is often a cosmic connection between what we feel and what the Earth does all around us. Perhaps the timing of that wind was a coincidence, or perhaps it was a tiny piece of my little girl touching me in the only way that she can now. Either way, my eyes were dried and I was able to read on. " When you are quiet, I think with you." Is this why I haven't been able to enjoy listening to music or my old pals on NPR for four months? Or why most noises and superfluous conversations have been especially grating to me? What was with this book? I brought it along with the intent of telling Charlotte that I loved her and would never let her memory go, but somewhere between the lines on the pages and the swaying mama tree above me, the tables had turned. This sweet little book has pictures of parent animals guiding their babies with messages like, "When you aren't sure, you'll feel me near. When you are scared, I will be here." It was there, in the woods, under that scarred-like-me tree, that I realized I'd had it backwards. Our babies teach us strength in their helplessness. We learn to do difficult things like changing diapers, working after sleepless nights, saying goodbye, holding their ashes, not for them, but because of them. Our children teach us how to be strong even when they aren't able to be with us. Charlotte has been guiding me to higher ground all along. I finished reading the story to the baby tree, then gently tucked my stone with a message to Charlotte into the crevice between its mama's roots. I nestled two rocks collected by Jack and Sam next to their sister's. My mind wandered to thoughts of an interview I have scheduled tomorrow and I pushed them out of my head. I had a whole path laid out before losing Charlotte and I am ridden with guilt for wanting to return to the ease of that mapped out existence. Thinking about career goals, personal bests, and my "five year plan" seems trivial when a life was lost. I looked up from my plodding feet and Charlotte had one more sign in store for me. It was, quite literally, a signpost, as if at this point she couldn't trust me to metaphors. "Please stay on trail." Good luck on the interview tomorrow, mom. Your path is my path, so stick to it. Thanks, Charlie.

BY HEATHER CARNAGHAN

Today I did something that I never thought that I would be able to do. I returned to the hospital where I gave birth to my daughter, stillborn at 38 weeks. My palms were so sweaty that they turned the corner of the cardboard box I held to mush. What could possibly make this freshly-grieving “loss mom” sit in a labor and delivery waiting room sandwiched between two women having contractions? My love for Charlotte. Charlotte never cried. She never spoke her first word, but in the three months since she died, her little life has spoken with more volume in my own than anyone I have ever known. Her message has been clear: don’t let this break you, mom, let it mold you into something new. I heard it loud and clear when I unearthed my wedding dress amidst a grief-induced fury of cleaning projects. A long-forgotten sewing machine sat on top of the dress box. I had never used it for anything but a strait line on a curtain...and if you’ve seen my curtains, you’re probably chuckling because they are anything but strait. I moved the machine and took my dress out of its box. This beautiful, sparkling gown was worn once and would only ever be worn once. I’m sure Charlotte would have been as stubborn as her mom and chosen her own wedding gown one day, but I sure would have liked to play dress-up with her in mine. I thought about all of the dresses that she’d miss out on: birthday dresses, prom dresses, maternity dresses. I thought about all of the babies who would miss those dresses. 1 in 4 pregnancies end in loss with 1 in 160 ending in stillbirth like Charlotte. I turned the sewing machine on and grabbed a sheet from the laundry pile. Just do it, mom. Four Youtube videos, two cut up onesies, and eight sheet-dress-attempts later, I felt ready to cut, pattern, and sew my wedding dress into tiny burial gowns for babies lost too soon. I posted my first attempt on Facebook. It was a simple gathered front dress with a tulle skirt and a big, happy bow right at the waist. It was Charlotte’s size. To my surprise, people began commenting that they had wedding dresses to donate, materials to share, and sewing expertise that they would like to volunteer. Suddenly I found myself busy, not dodging my grief in a cramped closet, but leading a project. In under one month, Charlotte’s little dress exploded into 26 wedding dress donations and eight sewing volunteers. Today I delivered the first batch of 29 layette sets for bereaved families to the labor and delivery wing. She gave me a beautiful reason to be strong and face the raw, visceral fear of returning to the same hospital I’d left empty handed just three months ago. I told you so, mom. Charlotte will never wear the dress I made for her. She will never wear a wedding dress or a maternity dress, but because of Charlotte, the Wrapped in Love Project was born and countless babies will be given the dignity of one beautiful dress to wear. This legacy isn’t one that I had planned (or ever hoped) for my little girl, but I am so deeply proud of her for inspiring it. Charlotte’s little life has already had big meaning and I look forward to seeing what else this amazing girl can stir up in us all. If you would like to find out more about the Wrapped in Love Project, donate a wedding dress, or volunteer to sew, please visit https://www.charlottespurpose.com/wrapped-in-love-project.html BY HEATHER CARNAGHAN My grandmother, Teresa Elizabeth, passed away when I was in high school. You were named for her. She was the first person that I really loved who died. My grandfather used to visit her grave often and, if we were in town, I’d ask to go with him. Each time, he would clear her grave of debris and place his calloused farmer’s hand on it sadly. He’d stare at her name, shaking his head as if he didn’t believe it could be carved there in granite, even after so many years. There would be a long quiet moment and then he’d say, “you’ve missed so much, Tee.” Tee was her nickname, for Teresa without an H.

I remember thinking how sad it was every time my grandpa said those words and how quickly they meant more and more loss over time. I never thought that I would whisper those words to my little girl. I never thought they’d mean missing out on the feel of your weight sleeping on my shoulder or introducing you to your brothers. The hurt of my grandmother’s death is softened by reminders of her life. The memory of her sparkling blue eyes as she laughed is a pillow that I fall back on when I miss her. When she was so sick that she couldn’t stand on her own, my grandfather draped her arms over his shoulders and danced her down the hallway humming their favorite Glenn Miller song. When he dipped her head back and kissed her, she giggled and those eyes sparkled one more time. You come from a long line of devoted people who love with a tremendous depth. There is nothing soft about losing you, Charlotte; I have no memory of your laugh or knowledge of your gaze. Stillbirth is full of so many unfinished edges. Those ragged shards snag my heart and steal my breath unexpectedly at every turn. I try to smooth them over with my own love for you. I write your name in the sand, the snow, the dirt. I remember how long we spent agonizing over a perfect name before I painted it across your nursery wall and how each tiny piece of clothing in this closet was picked just for you, my game-changing girl. In three months, I’ve written your story and lamented my own in verse, I’ve taken on projects and counseled and grieved with other mothers. I’ve completed two dozen random acts of kindness in your name and tried to heal my own heart by patching hearts for others. I've talked and cried with you on long hikes in the woods, some as startlingly cold as your skin. Soon I will return to my classroom, brimming with children and life. Returning will present new shards that I try to soften with love and an attempt to siphon some good from this goodbye. I will always clear my head of debris on this date and miss you. I will touch your urn, shaking my head in disbelief, and miss the time we were promised. There will always be love, but also a melancholy I can't shake. It has only been three months, sweet girl, but already, “you’ve missed so much, Charlie.” By Heather CarnaghanDear New Mama,

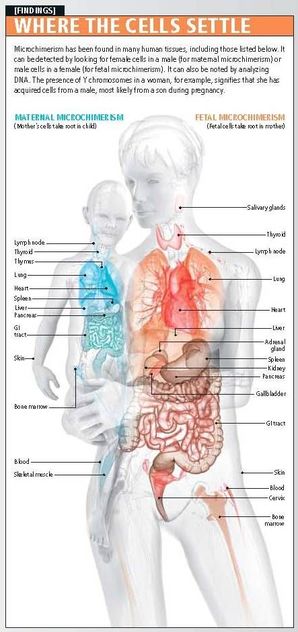

We were pregnant together, waddling around the same hallways at school and laughing about what bold little girls we would raise. We imagined maternity leave playdates and shared daycare possibilities when the time came that we would have to return to our classrooms. We just knew that they would skip off to kindergarten together some day and we’d have the unique journey of experiencing our daughters as both their mothers and their teachers. They were supposed to be friends. How could we know that my daughter would never meet yours? When I learned that you were going into labor, I texted my support. I wrote, “Thinking of you today. Can’t wait to meet your sweetheart!” I assured you that you were almost there and that your perfect girl would be wiggling in your arms before you knew it. I didn’t tell you that I was worried for you or that I stayed up all night terrified that my fate would be yours too. I told you that I love you, and I meant it because I wear my bare heart on my sleeve now in a way that I never did before. When you texted me that gorgeous baby picture, a flood of feelings knocked the wind out of me. I was relieved that your baby was safe and that babies could, indeed, still be safe. I was filled with love for this perfect little creature that you just brought into the world. I grinned from ear to ear. You, my sweet friend, just became a mommy for the first time, and I know that you are going to be so very good at it! My heart was brimming with excitement for you, but it broke a little for me too. I couldn’t help but think that every second of this baby’s life was one that Charlotte would never have. That first breath, the first cry, the first drink of milk. In one picture, she is resting on your bare shoulder. I could imagine the warmth of her against your skin and how wonderful that must feel. Charlotte only had my warmth, and like every piece of her, it was gone so quickly. I know that you will cherish every minute with your baby, because I know that, sometimes, you will still think of mine. I refuse to let my tragedy to keep me from celebrating your miracle. I want to hold your daughter and smell that little head of hair. I want to hear her sweet coos and wonder about who she will become. I want to celebrate when she rolls over, or makes a funny face when she first tastes peas. I was so happy when you said that you couldn’t wait for me to meet her, because, secretly, I was scared that you wouldn’t want me to. We both know that I will cry, and not in the joyful, “new baby, happy tears” way, but rather the “tsunami of grief meets the mountain of joy”, confused kind of way. I don’t want to be that mom who is always consumed by emotion, but the truth of the matter is that I am still very much consumed. I’ve gotten better at masking it. It has been two months since my baby was stillborn and every moment still hosts a conflicting dichotomy of feelings. I feel joy and sorrow at the same time and I never know what trigger might tip the scale in one direction or the other. Thank you for texting me when you didn’t have to. I know my story is the last one that you want to think about as you face childbirth. Thank you for sharing her picture and knowing that it would hurt a little, but mean a lot. Thank you for letting me be a part of your daughter’s life, just like I might have been before. Our first meeting may be teary, but you will both always know nothing but love from me. By Heather Carnaghan I looked around, confused. It was dark; I needed to turn on a light, but where was the switch? I was standing in the dining room of my own house, a house that I have lived in for six years now. I have high-fived that temperamental dimmer switch a thousand times before, but today I forgot where it was. It occured to me that I might be losing my mind. Grief doesn’t just take our emotions hostage, it also wreaks havoc on us physically. On October 21, 2017, I experienced the most traumatic event of my life. I say “in my life” because I sincerely hope that nothing can trump it. I was 38 weeks pregnant (that’s 8.5 months for those of you who only tie your own shoes before leaving the house each morning). My baby had been training in utero to become a parkour champion...until she just stopped. My baby’s little heart stopped beating. She was gone and I couldn’t imagine how my own heart could continue pumping so rapidly and not explode messily out of my chest. It didn't end there. You see, stillbirth isn’t one trauma. It’s a series of them. They come one after the other before you’re ready for them like balls hurtling from a pitching machine. Only you have no bat. No helmet to protect yourself. Labor. BAM. The silence. BAM. Telling my five and three year olds that their sister had died. BAM. Her due date arrived two weeks after I lost her. I felt utterly numb. I was broken and couldn’t form complete sentences that day. “Researchers completed an intriguing study that illustrates just how profound and widespread the effect of negative personal events can be and how your brain reacts to grief. Three finance professors from major business schools tracked the performance of 75,000 Danish companies in the 2 years before and after the CEO had experienced a family death. Financial performance declined 20% after the loss of a child, 15% after the death of a spouse, and almost 10% after the demise of any other family member.” -Dr. Thomas Crook Even though I felt lethargic and foggy, my brain was in overdrive. My amygdala, the part of my brain that is always on the lookout for pain, catalogues every instance of hurt so I won’t pick a fight with a tiger. When it detects imminent danger, it releases a chemical called cortisol. Cortisol elevates your heart rate so blood will race to all the muscles needed to protect yourself or run away from the source of alarm. The problem is, the amygdala doesn’t distinguish between physical and emotional threats of pain. When my doctor said that Charlotte’s heart had stopped, my amygdala logged this trauma and started firing like a trigger happy bodyguard. It fired every time I passed her empty crib or opened a sympathy card or saw a pregnant belly brimming with life. "TIGER, TIGER, TIGER!" Cortisol levels may exceed ten to twenty percent more than is typical during prolonged periods of stress. With cortisol constantly pumping blood to my fight or flight zones, there was little left for systems that weren't essential in defending myself against a giant cat attack. Digestion, concentration, memory. Arielle Schwartz, developer of Resilience-Informed Therapy & author of The Complex PTSD Workbook, says that “when stress cortisols are at their highest it is common to feel numb, cut-off, and disconnected.” Sound familiar? I eventually found the dimmer switch and I know I will eventually find the strength to carry the loss of my daughter. It’s starts with telling her story. With each telling, I retrain my amygdala, reminding it that Charlotte is no tiger. My brain is resilient. "Cultivating resilience is unrelated to the clichéd notion of time healing all wounds; overcoming is not the end goal. Instead of moving on, it's about living with what has happened. A resilient person is emotionally and psychologically flexible enough to allow the effects of a traumatic episode into her life, to "receive the shattering," and use those effects for healing. This means accepting the feelings of despair, but also remaining open to the possibility of love and connection." -Emily Rapp Black Each time I remember her hiccups and how they felt in the base of my belly or recall the joy I felt when the doctor said that she was a girl, I replace a little bit of the fight or flight cortisol with a gentler, happier chemical called serotonin. I rewire my grief brain by reminding myself to look for the good, and there is so much good that is left. I only wish that Charlotte was here to witness it with me. By Heather Carnaghan When my daughter was stillborn, friends and family reached out in countless thoughtful ways to show that they cared. They brought meals to fill our bellies, sent cards to offer condolences, and gifted trinkets to help us remember Charlotte. The overwhelming majority of those well-wishers suggested that she would "be in our hearts forever". This metaphor is truly a beautiful one: I will hold my child in my heart by honoring her existence and she will live on as I revisit those few, but meaningful memories of her. What they likely didn't realize, is that their kind sentiment actually has some pretty legitimate scientific backing. Charlotte's stillbirth was a particularly rare one in which, after a battery of tests and review of all available medical files, there just wasn't an answer regarding the cause of her death. I decided to read everything I could in the hopes of understanding those tests and identifying even a glimmer of an answer. Most pre-labor stillbirths are caused by placental or cord issues, so this seemed like an important place to begin.  The placenta is an organ that is shared by mother and baby during the pregnancy. (Science nerd moment: Can you believe our bodies construct a whole new organ for each of our children? Talk about the ultimate birthday gift!) We typically think of the placenta and umbilical cord as providing nutrients to the baby, but it does so much more. It actually allows cells to pass between the mother and her child. In a study at Leiden University Medical Center, pathologists found cells with Y chromosomes in autopsies done on women who died during or shortly after pregnancy. Why is this interesting? Cells with Y chromosomes are male cells and should not exist in a female body. Each of the 26 women had been carrying sons. Scientists believe that this is evidence of fetal microchimerism, or the passage of fetal cells to the mother's body. (History nerd moment: "microchimerism" is named after the chimera, an odd creature in Greek mythology with three heads, one of a goat, one of a lion, and one of a dragon.) The finding that was most surprising to me in this study was where the cells were found.  The pathologists found these rogue little baby boy cells in every organ that they tested. The cells had developed into functioning tissue in each of the organs. Fetal cells in the brain developed into brain tissue, fetal cells in the kidneys became kidney tissue, and fetal cells in the heart became heart tissue. The cells of these baby boys were, literally, a part of their mothers' beating hearts. Even more amazing yet: these cells have been found to be quick to spread and extremely long lasting. They have been detected as early as seven weeks into a pregnancy and may last a lifetime. One study found definitive evidence of fetal cells in a mother who had given birth to her son 27 years prior! Dr. Nelson and her colleagues at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center believe that fetal microchimerism is "very common, if not universal" as they found these cells in 63% of subjects in a 2012 study. The scientists theorize that the baby may be able to manipulate the mother to some degree in order to help them thrive (for example, sending messages to produce more milk, keep them warmer, or provide more resources for their growth). So the next time you suggest to a grieving mother that her beloved little one will be in her heart forever, say it like you mean it. Then tell her that he'll be in her lungs, kidneys, and brain too. Science has your back. |

Details

Heather CarnaghanHeather is an educator, writer, artist, and most of all, mother of four. Her three boys inspire joy in her life and writing. Heather's eagerly awaited daughter was stillborn in October of 2017, which focused her creative energy on grief and healing. She created and maintains CharlottesPurpose.com, a website dedicated to dealing with grief positively. Archives

July 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed